89 years old man brought to A&E by ambulance after falling backwards from an escalator as he stepped on it. He sustained head and chest injuries. On examination he was tender on anterior chest wall on the left side but there was no surgical emphysema or suspicion of flail segment. There was good air entry in both lungs and oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

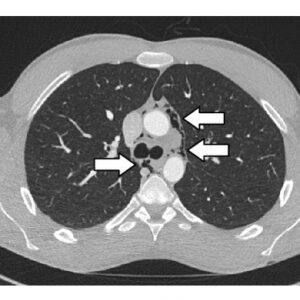

On trauma CT scans (PAN CT) he was found to have multiple rib fractures (1-4 ribs left side and 1st rib on right side). CT scan also revealed pneumomediastinum and small haemathorax (which did not need chest drain). There was no pneumothorax.

My learning:

Pathophysiology of pneumomediastinum

Pneumomediastinum is defined as presence of air or other gases in the mediastinum.

It may result from any of the following four mechanisms: [1]

- By direct air leak from rupture of the larynx, trachea, bronchus, or oesophagus into the mediastinum.

- By the “Macklin effect,”. A sudden increase in intrathoracic pressure results in alveolar rupture, with air dissecting along broncho-vascular sheaths, and then spreading into the mediastinum [2].The “Macklin effect” is involved in blunt traumatic pneumomediastinum. It is also seen in other conditions such as asthma exacerbations, positive pressure ventilation, and Valsalva manoeuvres

- By perforation of a hollow abdominal viscus with subsequent dissection of air into the mediastinum via the diaphragmatic hiatus

- By air which reaches the mediastinum through and along the potential spaces and fascial planes of the neck, such as in facial trauma.

Traumatic injuries especially blunt thoracic trauma is responsible for majority of cases of pneumomediastinum with the highest prevalence is seen in patients involved in high-speed motor vehicle accidents [3].

Clinical features:

The most common presenting symptom is chest pain, which is typically retrosternal and pleuritic in nature and may radiate to the neck, shoulders, and arms. Other less common symptoms are dyspnoea and dysphagia [4].

Physical examination can be normal in up to 30% of patients with pneumomediastinum. Signs suggestive of pneumomediastinum include subcutaneous emphysema and the “Hamman’s sign” which is a crunching, rasping sound, synchronous with the heartbeat, heard over the precordium [5].

Distended neck veins can be seen in tension pneumomediastinum if the escaped air compromises venous return.

Investigations:

Chest X ray:

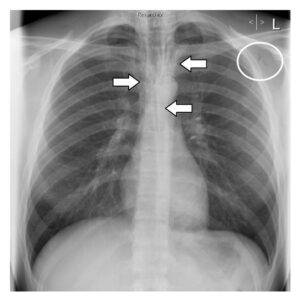

Radiographic signs of pneumomediastinum include lucent streaks of gas that outline mediastinal structures and often extend into the neck or chest wall [6].

(X ray images at the bottom of this post)

The radiograph should be examined for any evidence of associated pneumothorax, which can be present in up to 84% of patients [7].

CT chest:

The overall sensitivity and specificity of computed tomography for major aerodigestive tract injury is 100% and 85%, respectively [7].

Computed tomography findings suggestive of a major airway injury include airway irregularity, disruption of the cartilage or tracheal wall, focal thickening or indistinctness of the trachea or main bronchi, laryngeal disruption, and concurrent pneumoperitoneum on computed tomography of the abdomen.

Management:

Pneumomediastinum alone does not seem to have major clinical significance. Trauma patients should be treated on the basis of the overall clinical findings, associated injuries and imaging findings.

Most patients with major aerodigestive tract injuries undergo primary repair, although good results using selective nonoperative management have been reported [8].

Prophylactic intravenous antibiotic therapy with a broad-spectrum agent should be given to all patients with major aerodigestive tract injuries due to the risk of mediastinitis.

Patients with an isolated pneumomediastinum without other injuries may be treated conservatively with analgesia, rest, and an avoidance of manoeuvres that increase pulmonary pressure (Valsalva or forced expiration).

An isolated pneumomediastinum usually resolves within 2 to 15 days without consequences [9].

References:

1.Pneumomediastinum in blunt chest trauma: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Emerg Med.Mansella G, Bingisser R, Nickel CH.2014;2014:685381. doi:10.1155/2014/685381

2.The Macklin effect: a frequent etiology for pneumomediastinum in severe blunt chest trauma. Chest. Wintermark M, Schnyder P.2001;120(2):543–547.

3.Pneumomediastinum: etiology and a guide to diagnosis and treatment.

Banki F, Estrera AL, Harrison RG, Miller CC 3rd, Leake SS, Mitchell KG, Khalil K, Safi HJ, Kaiser LR

Am J Surg. 2013 Dec; 206(6):1001-6

4.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: time for consensus. North American Journal of Medical Sciences.

Sahni S, Verma S, Grullon J, Esquire A, Patel P, Talwar A.

2013;5(8):460–464.

5.Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Hamman L.

1939;64

6.Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs.

Bejvan SM, Godwin JD

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996 May; 166(5):1041-8.

7.The evaluation of pneumomediastinum in blunt trauma patients.

Dissanaike S, Shalhub S, Jurkovich GJ

J Trauma. 2008 Dec; 65(6):1340-5.

8.Blunt tracheobronchial injuries: treatment and outcomes.

Kiser AC, O’Brien SM, Detterbeck FC

Ann Thorac Surg. 2001 Jun; 71(6):2059-65.

9.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: is it a rare cause of chest pain?

Yellin A, Gapany-Gapanavicius M, Lieberman Y

Thorax. 1983 May; 38(5):383-5.

Chest X-ray showing air outlining mediastinal structures (arrows) and subcutaneous emphysema in the area of the left axilla